Community Internet Handbook

Why community broadband?

Whilst a glance at a price comparison site suggests a vaguely competitive market, the truth is more complex. Most broadband providers are reliant on one company – Openreach – for their infrastructure, and all mobile providers are reliant on one of the big four – BT/EE, Virgin Media O2, Vodafone, or Three. Rather than relying on a broken market model, we believe that a better approach is to help communities to create and own their internet access.

As this handbook sets out, communities are best placed to determine where the greatest need is, and the most appropriate solutions for them. For instance, a landlord signing an exclusivity deal with an internet provider in their tower block may work for them personally, it may not be efficient nor sufficient for tenants. Similarly, we’ve seen great innovation in rural areas which have built community broadband initiatives in response to a lack of will from national providers.

How to use this handbook

For community practitioners:

Take a look at our community engagement approach

Consider which technical solutions might work best for your area or community

Review our approach and learnings to help build a successful model

For local and combined authorities:

Review our policy recommendations to see how you can foster local innovation in your area

Take a look at our community engagement approach

Look at the technical solutions we’ve outlined to see which you could support locally

For policymakers:

Take a look at our case studies

Review our recommendations to see how you can foster local innovation in your area

Use our health benefits model to make the case for providing cheaper internet access

Background

The cost of living crisis caused a dramatic increase in household expenditure across the board, with inflation peaking at over 11%. The costs of getting online, however, increased by an even greater amount – with broadband operators implementing above-inflation price rises.

It has been acknowledged by Government that “access to the internet is increasingly essential for full participation in society.” This is true – many basic public services have moved to a digital-by-default model, whilst it is rare to find paper copies of homework in schools. Entertainment, too, has seen a dramatic shift from the internet, with streaming services like Netflix and Spotify quickly replacing DVDs and CDs.

However, we believe we need to go a step – we think internet access is an essential utility. We believe that we need a stronger package of protections for consumers, allowing everyone to access affordable broadband. To meet everyone’s needs we also believe that the broadband market needs diversifying, including allowing communities to develop and manage their own provision.

There are many existing policies and programs which seek to support people with their internet costs. However, these are often difficult to access, tied to certain eligibility criteria, or aren’t fit for purpose. Social tariffs, for instance, are typically only available to those on Universal Credit and certain other benefits – excluding those who might be just above the threshold, whilst ignoring the significant financial pressures that people with no recourse to public funds face, such as people seeking asylum.

We worked with Impact on Urban Health to identify a suitable location and technical solution to develop and trial free, community owned broadband. We partnered with Community Tech Aid who provided local knowledge and on-the-ground support, and together with Jangala, we developed a model for a pilot which would have provided households with ‘WiFi in a box.’

1 Julia Lopez, ‘Written Question from Cat Smith MP to the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, UIN 18501.’, 13 March 2024, https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-questions/detail/2024-03-13/18501.

Case Studies

-

Researchers and businesses are working together in Sheffield to deliver a free broadband pilot on the Dryden Estate. The project has been approved for an initial three years of funding, and is supported by The University of Sheffield, a local ISP, Pine Media, the Digital Poverty Alliance, as well as local business leaders. The initiative was approved with the intention of addressing local inequalities and increasing employment opportunities.

One of the challenges that the project faced was the wayleave process – essentially, the right to access and dig up land to install cables. Whilst the process of installing the cables themselves is relatively straightforward, taking about six weeks, the sign-off period can take significantly longer depending on the scale of the project, the landowners’ concerns, and any existing infrastructure.

The project was initially approved in 2022, but they saw slow growth in sign-ups in the initial phases. This may have been due to a lack of awareness about what the project would offer. Another possible factor for the slow sign-up was the initial plan to restrict access to certain websites. However, this approach has since been scrapped, and removing the monitoring of sites seems to have improved the project’s reception.

They are now exploring a second site to gain more sign-ups for the project, and are working with students at the local universities to promote sign-ups. Two local residents will also be employed to provide the first line of support and information.

-

B4RN – pronounced ‘barn’ – has taken a community-led approach to understanding the physical barriers to broadband deployment. This enables B4RN to deliver broadband at more affordable rates than market leaders. B4RN’s model relies on close involvement with the community to deploy infrastructure. They work with volunteers to lay cables and local investors to fund the developments.

B4RN offers both a social tariff – priced at £15 per month for those receiving Council Tax Support – and residential tariffs at £33 per month. Both tariffs offer a 1Gbps service, though customers can pay up to £150 per month for a 10Gbs service.

Whilst B4RN does not provide free connections by default, they offer investors the option to donate free connections to a customer or property. B4RN also offers community connections – offering discretionary pricing to small primary schools or other local assets like village halls.

-

CTNY developed a wireless network model called a Portable Network Kit, or PNK. A form of ‘WiFi in a box,’ the PNK primarily works as an educational tool, but can also be used as a standalone network in emergency situations.

The PNK is used to train members of the local community – helping them to understand how networks operate and can be maintained. This helps to build a long term, embedded understanding of what works, so that knowledge isn’t lost if someone moves out of the area. CTNY also operates a Community Tech Lab to provide further digital skills training to the local community.

Unlike many community internet movements in the UK, CTNY receives funding from a wide range of philanthropic organisations, such as the Ford Foundation and the Internet Society Foundation.

-

NYC Mesh is a community project which offers low cost internet access via the development of a mesh network. When members join, they provide a rooftop router, which is then connected to a series of other routers across the city.

The mesh model allows for the development of a wide-ranging network with significant scale to feasibly rival market providers. Whilst members are not required to pay, NYC Mesh encourages regular monthly payments to ensure the financial sustainability of the project.

A model like the one that NYC Mesh uses is best suited to densely populated urban areas, as a weakness of the model is that a connection requires a clear ‘line of sight’ view to the rooftop router. This would likely not be possible to achieve in smaller towns or rural areas in the UK.

Developing community broadband: our approach and learning

Setting out your aims and objectives

To raise funding and generate momentum behind your project, it is important to identify what your core aims and objectives for delivering free or affordable internet access are. For instance, you may want to help families in poverty access key services, like healthcare, education, and employment opportunities. You might want to deliver the project as a means of tackling social isolation and contributing to community cohesion.

“Building a community broadband model is like a restaurant menu. There may be many things that look appealing, and many which work well for you. But ultimately it’s up to you to decide what are the most important things on the menu. You may need to compromise to build a viable project.”

Anna Dent, Head of Research

If your project isn’t self-funding, breaking this down into clearer aims and objectives can help to win funding for your project.

Our aims were to:

To assess the relationship between internet access and the social determinants of health;

To explore the scalability of community owned models of internet access;

To develop a model which would be sustainable, both with regards to governance and finance.

Choosing the right area

Choosing the right area or population is arguably the most important step – and can be one of the most time consuming. If you don’t already know who and where you’re looking to support, it can be tricky to identify where the greatest need is. There would be little point in delivering an internet access pilot in a high-income area with good broadband connections but you might need to find ways to understand what’s happening locally.

Initial steps

Due to funding requirements, we knew we would be focusing on Lambeth or Southwark in South London for the development of our work. This significantly narrowed the search for appropriate areas.

At present, there is no nationally accepted measure of digital exclusion. The Government’s most recent measure is outdated, and simply asks people whether they have been online “in the past three months.” In the absence of a robust, modern measure, we made use of three datasets to help identify areas with the greatest need. These were:

The Digital Exclusion Risk Index, developed by Greater Manchester Combined Authority. As a risk index, this dataset pooled various demographic data that are associated with digital exclusion to give a picture of where people may be digitally excluded. However, it is not a direct measure of digital exclusion itself.

London Digital Exclusion Map, developed by Loti. A similar model which uses proxy indicators to identify areas which may experience digital exclusion, but is not a direct measure of digital exclusion itself.

The Impact on Urban Health Community Insights Map, which incorporates data on internet usage, download speeds, and classifies people by their internet usage.

These datasets varied in approach and methodology, so we produced a combined model from these data to get a greater understanding of need.

Methods

We built a model to triangulate the three models, as they each had their own benefits and drawbacks. For instance, DERI and Loti focused more on demographics, whilst the IoUH tool considered internet speeds and how people use the internet.

Each of the datasets were overlaid and we were able to rank them, identifying which areas within Lambeth and Southwark scored highly in all three models.

Quality Checks

We checked for anomalies in our data – for instance, an area that we know to be high income and well connected appearing in the merged dataset. To sense check this, we later shared the data with our funding and delivery partners, who agreed that the places we shortlisted made sense.

Shortlisting

The top ten were then used as a basis for conversations with local and community organisations, so that we were having those conversations on a relatively short list rather than presenting an entire borough’s worth of areas.

At this stage, we also added in other considerations such as local housing stock - connecting a street of terraced houses with different ownership and tenancy arrangements for example would potentially be more complex than a single tower block with one landlord.

Using something like WiFi in a box – the model used by the charity Jangala – the housing stock doesn’t matter as much, but at this stage we weren’t sure which technical solution we were actually going to use.

We also needed to consider what community organisations already existed and might be interested in working with us. But other organisations considering this may start with a community organisation first, which may then dictate the location, whilst others may start with the technical solution.

Choosing the right technical solution

Digital exclusion is a complex policy issue. As such, there isn’t one solution which works for everyone.

Our approach was to:

Convene experts;

Understand the legal and regulatory barriers;

Identify potential technical solutions;

Check the feasibility of these products;

Examine potential financing routes.

Convening experts

We organised two sessions with experts in the field to gauge opinions and explore what options were most feasible. The first of these was held in London, and a second in Hebden Bridge, Yorkshire. We organised the London event ourselves, whereas for Hebden Bridge, we organised a talk at ‘Wuthering Bytes’. We also took on freelance advice from a technologist, who scoped some potential solutions for us.

Legal and regulatory barriers

There are various legal complications which can arise from trying to establish an affordable internet provider – not all of which we were aware of in advance.

Terms and conditions

Quickly dismissed as an idea was the use of business internet connections to provide access to a wider community. Setting up an ISP via a business connection would be in violation of the ISP’s terms and conditions.

However, some ISPs – such as B4RN – have started to launch services which provide internet access to community assets, such as village halls. As suggested by Kat Dixon in her report for the Data Poverty Lab, these ‘community tariffs’ could be a route to providing affordable connections to the local community.

Wayleaves and leases

For physical infrastructure such as fibre connections, getting wayleave or lease permission is crucial – but time-consuming and expensive. Wayleave is the right to dig up land in order to lay cables. Wayleaves typically involve payment to the landowner, though it is possible (if not likely) that in some areas the landowner may waive this cost for a community-focused project. Wayleaves are used for infrastructure such as cables. Leases tend to be time-limited and are more common for the deployment of mobile masts.

Some parts of the country have developed initiatives to speed up the wayleave process. For example, the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology identify Glasgow, Lewisham, and Wolverhampton as three council areas where new processes have been introduced to improve wayleave access and foster innovation. Nevertheless, for most of the country, the process is slow and as such fixed physical infrastructure may prove to be non-viable.

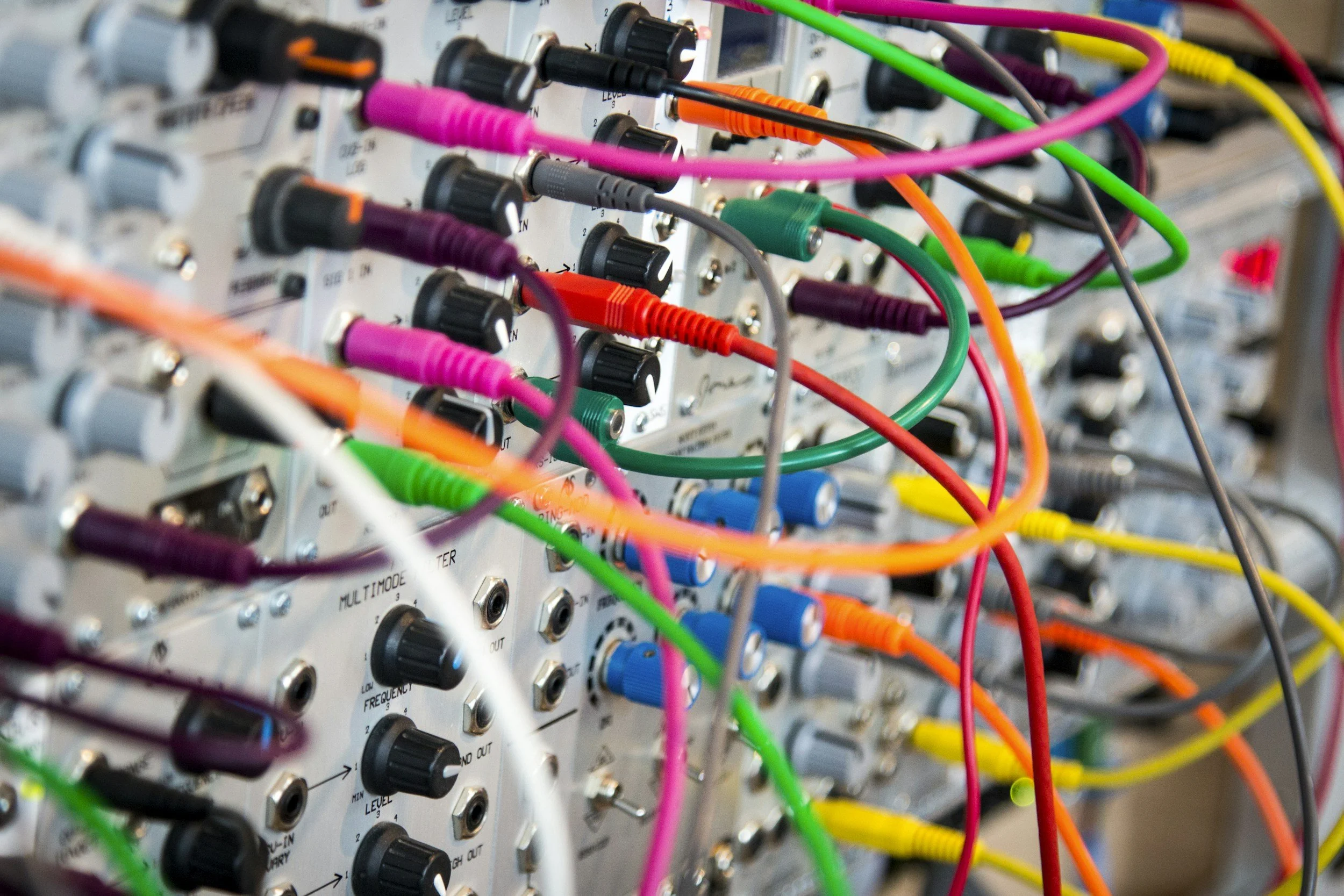

[04 ]

[05 ]

[06]

Identifying potential solutions and scoping feasibility

Working with the expert groups identified above, we identified several potential solutions that we might want to consider. Here, we rank these from least likely to most likely. This however is a reflection on our project – you may reach different conclusions in your area.

‘Hotel WiFi’

One model proposed was ‘hotel wifi’ – in essence, running fibre connections to a building and setting up the necessary wireless infrastructure. All households in the building would be connected to the same network, in line with how access to the internet works in a hotel.

Home routers

A simpler idea was to provide routers to households. In theory, this would remove the need to install new connections to households.

Creating a Mobile Virtual Network Operator (MVNO)

Most mobile networks in the UK are MVNOs. They do not own or maintain their own mobile masts or have direct access to wireless spectrum. Instead, they sign agreements with one of the four major network providers and grant access to their wireless spectrum instead.

‘Wifi in a box’

This solution is similar to that of the MVNO. However, instead of setting up a full network operator, this option just provides households with a SIM-enabled router.

From these technical solutions, we opted for the ‘wifi in a box’ model, as it offered flexibility, easy set-up, and a relatively low-cost.

It is important to note that we also scoped other potential solutions, such as those which used emerging technologies or more novel solutions. These included mesh wifi networks – as seen in the Mesh NYC project – and wifi over coaxial cables. We ultimately decided not to go with these due to time and cost constraints – but when considering the appropriate solution for your community, these could provide inspiration for what is possible.

Choosing the right partners

Having identified the technical solution we wanted to pursue, we moved on to explore potential local delivery partners.

There were a few key aspects to consider here:

Tech experience

Who has experience in building and delivering this technology at a low cost?

Do they have a track record of long-term support?

Financing

How could the tech be funded?

Community engagement

How do they work with communities to support their technology needs?

Do they take a holistic approach to digital access and inclusion?

Finding the right partners

Through our research into technical solutions, we identified Jangala as an organisation who are leading on the ‘WiFi in a box’ model.

As we were finalising our technical approach, we learnt that Jangala were developing a nationwide rollout of their ‘Get Box’ model, funded by Virgin Media O2. We spoke to Jangala about taking part in this project, ultimately leading to our partnership together.

To identify potential community delivery partners, we reached out to Good Things Foundation, the digital inclusion charity. Good Things Foundation supports a network of thousands of hyperlocal community organisations to deliver digital inclusion support.

They helped us to identify an initial shortlist of community organisations who might be interested in delivering the diary study and pilot project with us.

We developed a brief and an expression of interest form, which we shared with these organisations. Our brief set out three key criteria:

Trust – how did they work with the community to establish trust?

Skills – what work did they do to ensure people could use the technology effectively and safely?

Location – would the organisation be well placed and accessible to our chosen area?

Diary study

To understand more about the community we were planning to work with, their current access to the internet and the kinds of tasks and activities they do online, we organised a month-long diary study, working with ten households in the community. In particular, we were interested in how their usage linked to the social determinants of health.

Methods

We designed several engagement routes for the diary study process. These included:

Written diary entries;

WhatsApp voice notes;

WhatsApp messages;

Video responses;

Phone calls;

In-person catch-ups.

We wanted to make this process as easy as possible for people to participate in. Rather than saying ‘the only way to participate is to do an online form or an interview,’ which would have been about what worked best for us, we wanted to make it open to people’s preferences and what worked for them.

Opening up these routes increased the likelihood of getting more, richer responses. Whilst it is more work to collate and analyse, we believe that our approach ultimately led to better data and was therefore worth the extra effort.

“It’s more convenient to offer people the option to do a voice note when they’re, for instance, going to drop off the kids, or to write in a diary in the evening. People have different lives and their approaches will vary.” – Anna Dent, Head of Research, Promising Trouble

Community communication

A member of our team attended some of the diary study briefing sessions to provide a name and a face to the project. This was done to build trust between participants, the community organisation, and us as researchers.

We also wanted to be there to communicate the complexity of the project. We needed to ensure that the community understood that participation in the diary study did not guarantee that the pilot would go ahead.

Indeed, when putting together your project, you need to consider all the options from the outset and take care not to raise expectations which might not be met. This is particularly important when working with people who may be on low incomes, so as to not lead to reliance upon your project should it fall through.

Challenges and Recommendations

We faced numerous challenges in our attempts to establish a broadband pilot. Notably, at the time of writing we are still looking for funding to roll out the pilot in South London.

Here, we outline some of these challenges in greater detail, and how you might able to learn from them for the development of your work:

Further Recommendations

Location – you can start small! Start with small neighbourhoods rather than an entire town or city. Consider working in areas where political support for the project is likely to be greatest – for example, providing internet access to families with children receiving free school meals.

Governance – explore cooperative models as a route to community governance.

Health benefits – our work has begun to show the health benefits of internet access. Use this work to gain support for your project.

Engagement – work with the community to identify greatest need and the right solutions.